10:15 am

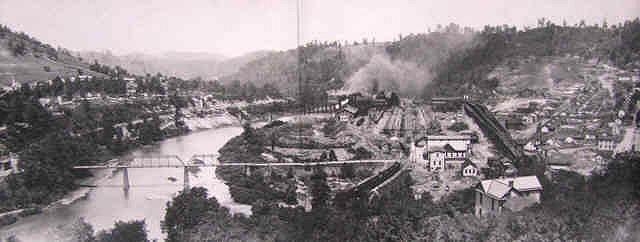

Outside #6

J.H. Leonard is just outside of the fan house and watches the trip of coal cars come out of the mine mouth, pass by the derailing switch, and begin to travel up the trestle toward the tipple. (McAteer, Inquiry) ◊

10:19 am

In East Monongah:

William Finley is standing on the street by the coal company’s office at the south side, not far from #6. (Inquiry)

10:20 am

Outside #6

Nick Smith is working at the forge in the blacksmith shop. (Inquiry)

Inside the fan house, the gauge for the fan pressure rises .4 inch. This is normal, typically caused either by general workings vibrations or the loaded trip of cars going, “with and against the current” of air being pushed through the mines. (Inquiry, Victor)

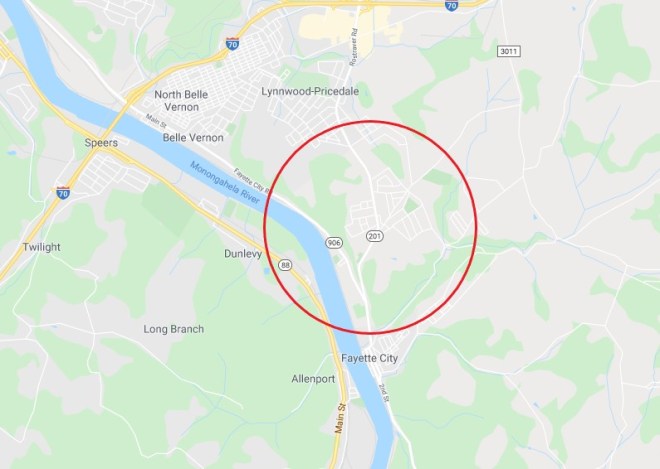

In Traction Park (between #6 and #8):

George Bice is walking down to the Traction Park interurban station to catch the trolley into Fairmont. George is a tracklayer in #8, but he is not scheduled to work today. (Inquiry)

Inside #8

Orazio DePetris notices a fire boss come into his area for a few moments and then leave. (Inquiry)

Angelo DePetris has just finished putting in a shot and begins picking from the roof. (Inquiry)

Peter and Stan Urban sit down to eat some lunch. (Inquiry)

Outside #8

Lee Curry, the stationary engineer, just finished dropping a trip of empty coal cars into #8 mine and has stopped it still. (Inquiry)

Carl Meredith is on the same loaded track, looking toward the mouth of #8 mine. (Inquiry)

On the opposite side of the river:

E.P Knight, #6 tipple foreman, is in the shanty under #6 tipple. He is talking on the phone with John Talbot in the shipping department discussing coal cars, or probably the lack thereof. (Inquiry)

Pat McDonald is walking on the haulage bridge, facing the mouth of #6. (Inquiry)

Outside #6 on the trestle:

The trip of cars gets stuck at the knuckle of the tipple; the rear car is about 50’ from the knuckle. (Inquiry)

10:21 am

A warning light in the engine room, connected to the main current line, which indicates that the train of cars is in motion turns off. (McAteer, Inquiry)

10:25 am

Outside #6

J.H. Leonard watches the stuck trip of cars and waits by the derailing switch. (McAteer, Inquiry)

Luther Toothman is on #2 tipple (directly opposite of #6). (Inquiry)

10:26 am

Christina Cerdelli is standing in the door of her home. (Inquiry) ◊

10:27 am

Levi Martin is at his home on Willow Tree Lane (just past Thoburn post office, above and behind #8). (Inquiry)

10:28 am

On the West side of Monongah:

George Bice reaches Traction Park interurban station. He is about 330 feet from #8 and ¼ mile from #6. (Inquiry) ◊

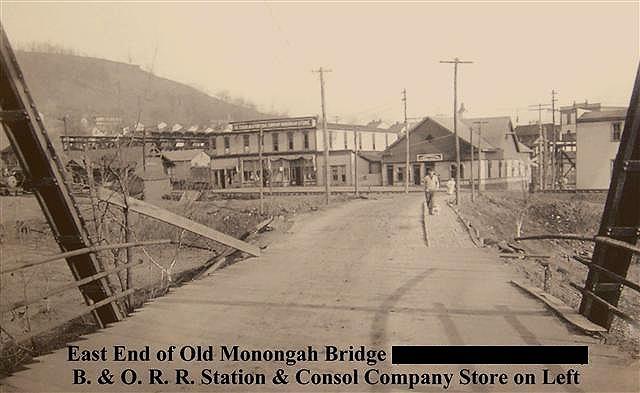

On the East side of Monongah:

George Peddicord is walking onto the Iron bridge with buckets of chains from the East end of town. (Inquiry) ◊

Outside #6:

Will Jenkins has just finished replacing one shoe on a horse in the blacksmith shop and is preparing to shoe the other foot. (Inquiry)

J.H Leonard hears a noise from fan house and, fearing the fan was stalling, turned away from the derailing switch and ran back to the fan house to check the fan engine. (McAteer, Inquiry)

10:29 am

Outside #6:

J.H Leonard barely gets into the fan house when he hears a large *snap*. (Inquiry)

At the top of #6 trestle:

The loaded tip of coal cars has been stuck for almost ten minutes when the coupling pin on the first car of the train snaps. (McAteer, Inquiry)

In #6 engine house:

Ed Fry notices the engine speed up once the trip breaks free of the rope. (Inquiry)

Across the river from #6:

E.P. Knight, who is still on the phone with Talbott, feels the #6 tipple jar and sees the wench rope jerk back. Before Knight can tell Talbott that the train broke loose, Talbott has already sat down the phone and started outside. (Inquiry)

On the trestle:

The loaded trip of cars begins careening back down the trestle toward the mine mouth. (McAteer, Inquiry)

Pat McDonald hears the trip break loose, turns and looks up to see it racing back down the trestle. He begins to sprint towards the derailing switch. (McAteer, Inquiry)

Outside #6:

J.H. Leonard turns around, runs out of the fan house and back toward the derailing switch. (McAteer, Inquiry)

Nick Smith watches the runaway trip speeding toward the #6 mouth from the blacksmith shop. (Inquiry)

The trip makes an “unusual noise”, startling the horse in the blacksmith shop causing the horse to trample Will Jenkins to the ground. (Inquiry)

Alonzo Shroyer is 50-60 feet away from the mine mouth and only notices the trip when it is passing right by him. (Inquiry)

J.H. Leonard makes it back to the derailing switch just in time to watch the last two cars go into the mine. (Inquiry)

In #6 engine house:

The lights in the engine room flicker off and back on. Ed Fry turns off the wench engine. (Inquiry)

At the mouth of #6:

J.H. Leonard thinks someone could get caught on the slope of the mine in the wake of the runaway train. He and Alonzo Shroyer run to the mouth of the mine and look down into the portal. Leonard braces himself for impact. (Inquiry)

Outside #6:

The power goes out in the blacksmith shop. (Inquiry)

Outside #8:

The interurban car, south-bound for Clarksburg, passes by and below the trestle to #8 mine mouth.

On the West side of Monongah, between #6 & #8:

George Bice sees the trolley heading south, passing by #8. He is worried he is too late and has missed the trolley into Fairmont. He turns north, toward #6, to see if it is already on its way to Fairmont. (Inquiry)

Inside #8:

The DePetris brothers are just bending over to pick up and load the coal they just shot down. (Inquiry)

Peter Urban is finishing up his lunch when he hears a noise in the distance and suggests to his brother, Stan, that they should run. Stan hears nothing over the noise of his work, shrugs off his brothers concerns and goes back to digging coal. (McAteer, Inquiry)

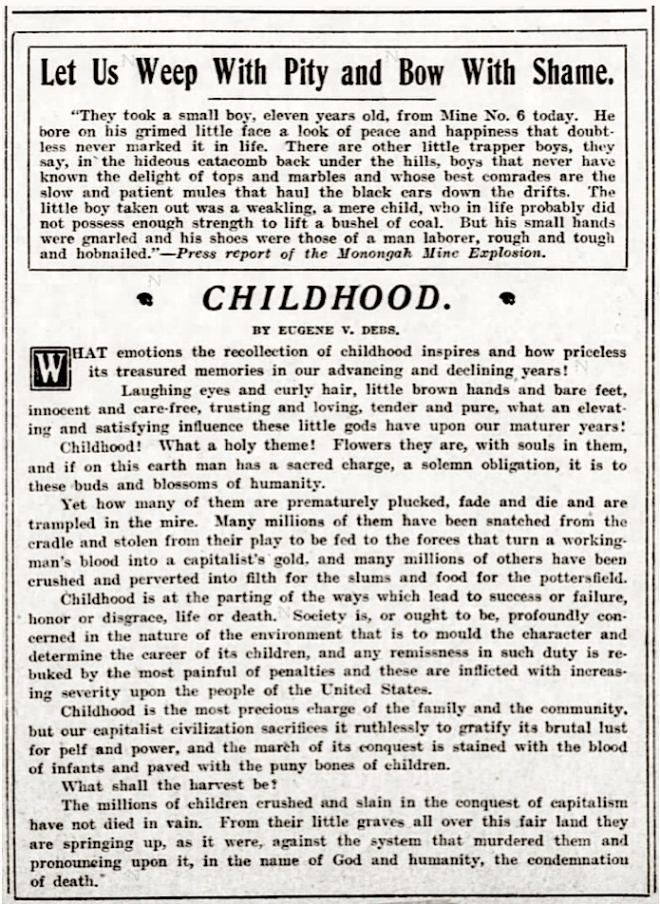

More on How Death Gloated!