Midnight – 3:15 am

In Fairmont:

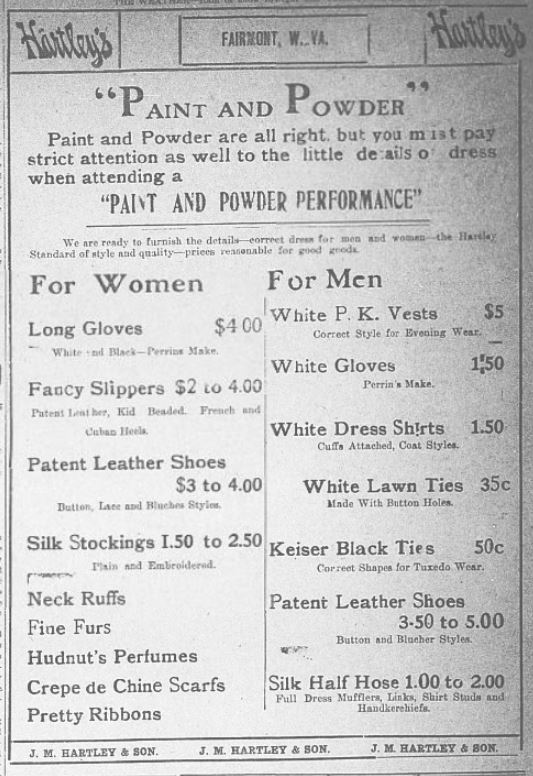

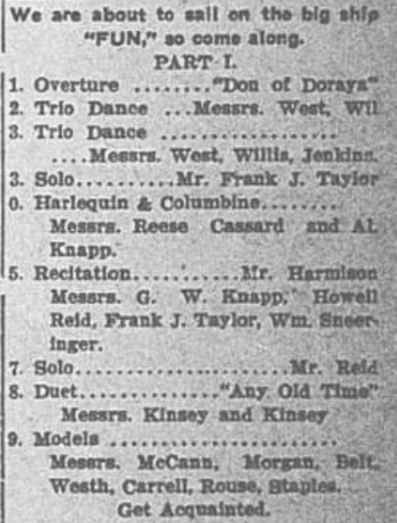

“About one hundred gentlemen comprising of Fairmont’s representative citizens, gave the Paint and Powder boys an elaborate reception at the Elks club between the hours of 12 and train time (3:15).” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 5)

“A splendid collection was served by Steward Pangle and speeches were made and responded to by the P.P. Boys.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 5)

“The boys rolled out of the station to the strain of “Maryland, My Maryland” played by Prof. Omen’s band and the lusty cheers of the delegation of Fairmonters there to see them off.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 5)

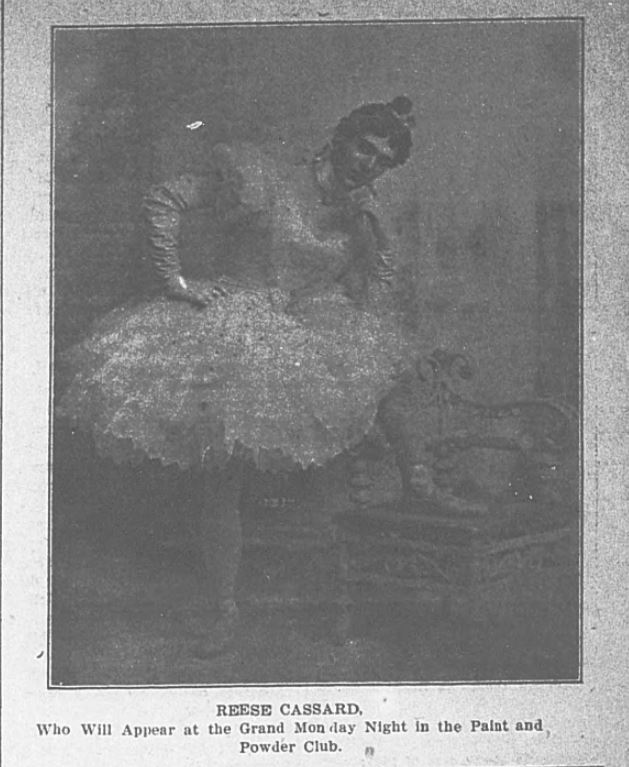

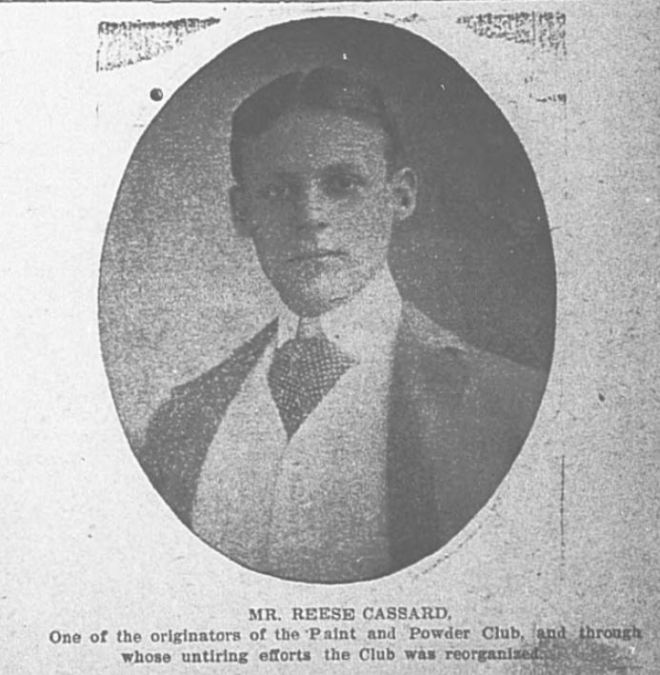

“Reese Cassard in his parting from the rear of the slowly moving train expressed most feelingly the grateful thanks of all the boys for the hearty and successful efforts made for their comfort and the generous applause for their work and said Fairmont is on the P&P annual itinerary as long as there is a P&P.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 5)

“Fairmont is indeed to be congratulated on this acquisition to her artistic entertainment, for she will now each year have the benefits of the Club’s annual production, not only from the enjoyment view point, but the proceeds going to some worthy Fairmont charity.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 5)

Morning

In Fairmont:

The Fairmont West Virginian reports the weather will be: Rain or snow tonight and Wednesday.

The West Virginia Joint Legislative Committee has arrived from Clarksburg to attend the hearings. (CDT 01.07.08 pg 1)

~10:30 am

In Fairmont:

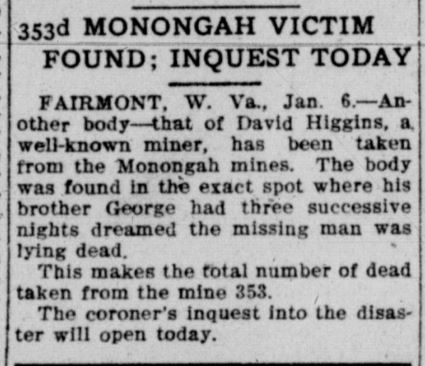

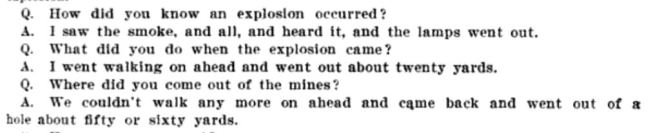

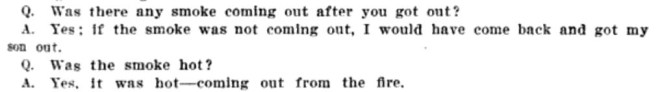

Testimonies continue in the Fairmont Courthouse. “The second day of the court inquiry was held in the Circuit Court room, where many listeners assembled eager to catch every word of evidence from the witness.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 1)

“William Vokolek, an attorney at law of Pittsburg, representative of the National Slavonic Society, is here to aid in any way that he can to arrive at the cause of the explosion. He is also settling claims of widows against the society. So far the society has distributed $250.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 1)

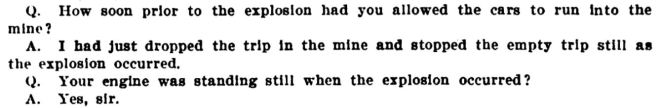

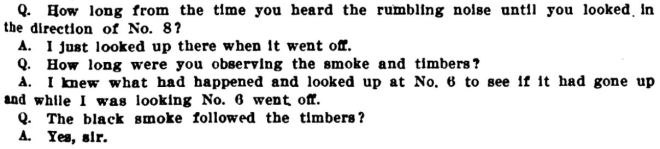

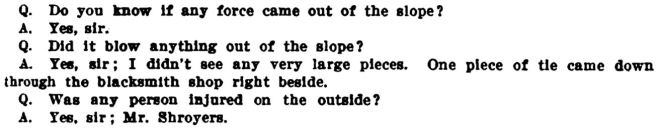

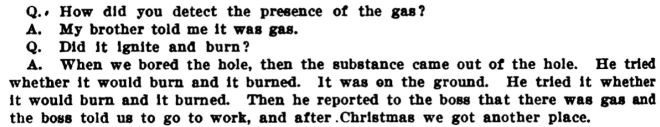

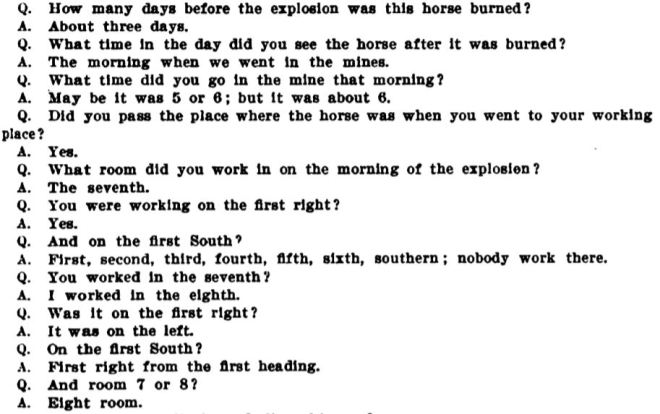

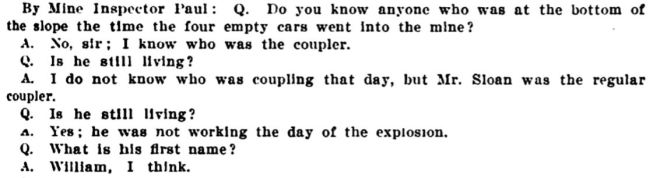

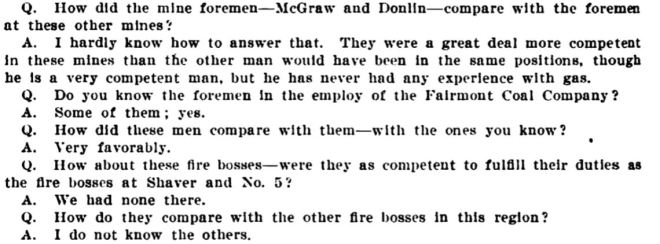

Alonzo Shroyer lives in Mill Fall, a hollow connected to Monongah, and works in the #6 blacksmith shop as a carpenter doing repair work. He is examined by Inspector Paul. (Inquiry)

Alonzo was only 50-60 feet from the mouth of #6 mine, closer to the fan and near the derailing switch, when the trip of cars broke loose. However, he did not actually see the trip until it was already passing him, so he made no attempt to throw the derailing switch. Once it passed him, he went “immediately to the mouth of the mine or near it.”

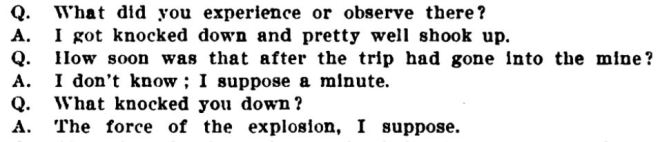

Alonzo thinks he was standing maybe 10 or 15 feet away from the mouth of the mine when the force knocked him down. His right ear was cut open in the fall “and a gash behind the ear to the bone”; he believes he was knocked against the derailing switch stand.

Alonzo also says that he thinks the runaway trip had time to get to the bottom of the mine slope.

Alonzo states that he heard no noises from the direction of #8. Once the trip passed, Alonzo intended to follow the trip into the mine and says he was on his way to the shop “to get a torch to follow the trip.”

He again estimates that it was around a minute from the time the trip passed him to the time of the explosion.

Alonzo states that he saw dark smoke coming from the mouth of the mine but neither saw nor felt signs of flame. Based on “the distance I went and where I went”, he estimates that the smoke must have continued coming out of the mine mouth for 4-5 minutes and agree that it could have been even longer than that.

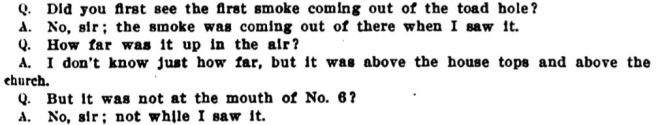

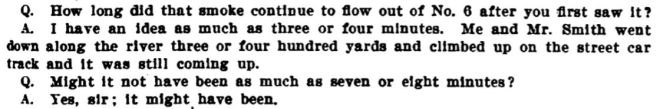

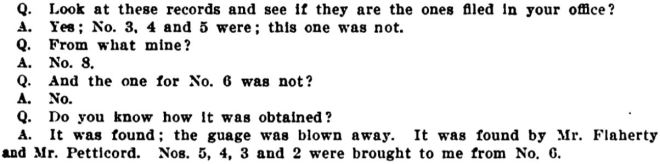

J.H. Leonard has lived in Monongah for 16 years and has been a fan operator at #6 for the past 6 or 7 years. He is examined by Inspector Paul.

Leonard was working on the 5th and confirms that the fan was running all day and hadn’t even been stopped “since the Sunday a week before” until that the evening of the 5th when it was stopped for 2 ½ hours.

Leonard says the explosion knocked him down and bruised his arm and ankle. “I crawled around above to a pile of old stuff there and there was a hole there and I let myself through down under the trestle.”

Leonard says that, to him, the mouth of the mine looked “like a big steam pipe”.

Leonard had gone into the fan house and oiled the fan only a 15-20 minutes prior to the explosion. “The oil sometimes stops in the cups on the wrist pin and it only takes a couple of minutes to get it hot. I run in to see if the oil was running.”

Leonard confirms that the fan has a pressure gauge to indicate and record the pressure. He says that it is normally the night shift operator who changes out the indicator cards. Leonard got his first experience in changing the card when he was working the night shift on Wednesday, Dec. 4th.

Leonard explains further that they feared someone, or perhaps a motor trip, was coming up the slope at the time the trip ran back into the mine on the very same track. He says he saw nor felt any sign of flame and the smoke was not hot.

Leonard does not believe that the smoke was blowing out for very long. “I crawled around there when it struck me and I was not long about it; I dropped down under the trestle and I don’t think I was there more than a minute until I came up and it was still blowing some.” He says there was no backward motion of the smoke getting sucked back into the mine, just a “continuous blow like a steam pipe.”

When he was hiding under the trestle, he pulled a piece of a coal car door over top of him; “I thought it would protect me.” He also saw Mr. Graves under there and says he was under there at the time of the explosion.”

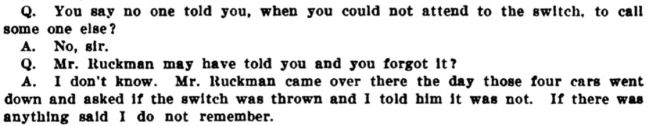

Inspector LaRue asks Leonard if he recalls LaRue’s visit to the mine and discussing the “matter of the throw-off switch”. Leonard recalls telling him that he could not properly attend to watching the derailing switch and that he had never received any orders from any “superior officers” to call someone over to watch the switch if he had to leave it unattended to tend to the fan engine. He did not call anyone over to watch the switch that morning as the “blacksmith was shoeing horses and I did not know there were two men there. There was only two carpenters there and they were both busy back of the fan house.”

Leonard is not sure of the speed of the fan at the time of the explosion other than “it was the same all morning before that.” He remained at the mine in charge of the fan.

The fan did not shut off on its own, according to Leonard, but was shut down by orders of Mr. Dean so that certain repairs could be made as quickly as possible. “It was not very long until it was started; maybe a half hour.” He states that the fan “had not been shut down since the Sunday a week before, until some one ordered me to shut it down to make that repair.”

Leonard estimates that the derailing switch is about 25-30 feet from the mouth of #6 and possibly 75 to 100 feet away from the fan house, though he has never measured the distance.

Leonard again states that he did not call anyone on the day of the explosion because “there were only two men close and one was shoeing a horse and the other was working back of the fan house. I did not see him at that time but he was working there, I know.” And he thought he had time to get back to the switch if needed.

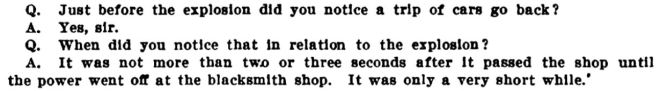

By the time Leonard reached the switch, however, the last two cars of the runaway trip were passing by him. He says that he does not know how many cars were part of that trip but the usual trip runs anywhere from 8-15 cars, nor does he recall seeing a water-car on that trip.

Leonard says that the normal fan engineer who runs the opposite shift is Michael McDonald but he was sick on that day, so it was run by Mr. Lambert.

Leonard states that the runaway trip of 4 cars he had mentioned earlier happened possibly a “week or two before” the explosions and that they wee just 4 empty cars which had been accidentally shoved back over the knuckle.

He goes on to say this pit boss was Mr. Donlin.

Leonard says that the mine foreman gives him “more instructions than anyone else, and about the fan, too. He always cautioned me to be very careful and keep it at a proper speed and see that nothing went wrong, regardless of anything else.” Leonard says that he obeyed the foreman’s orders about the switch and the fan.

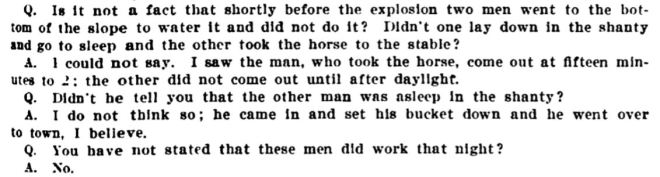

Inspector LaRue asks Leonard if he knows of anyone being sent into #6 to water the headings the night before the explosion (Dec. 5th) or coming out the morning of (Dec. 6th). Leonard responds that he worked the night of the 4th and on that night, “…there is a signal to let the men out of the pit, and a man came out. He was an Italian. He had a horse, and said he had been watering the track. Motorman Cooper came out in the morning.” Though he does not know what part of the mine was watered, he recalls this man came out around 1:45 a.m. because Mr. Donnelly “wanted to know the time the men came out. Mr. Cooper came out after daylight.”

Leonard can not testify to how frequently the tracks are watered because, “…I worked in the day time and they waster at night and on Sundays. Very frequently they water on Sunday. I think Saturday night and Sunday is the general time for watering.”

Leonard states that he knows that Fred Cooper watered the mines on the night of the 4th. He tells Inspector Paul that he had not seen any men or animals brought out that had been burnt by gas “for a good while”. He says that a year ago, “I saw a mule that had gotten its ears singed and they said it was by gas.”

Leonard tells Att. Lowe that he knows of no other explosions in the mine, big or small, prior to those on Dec. 6th.

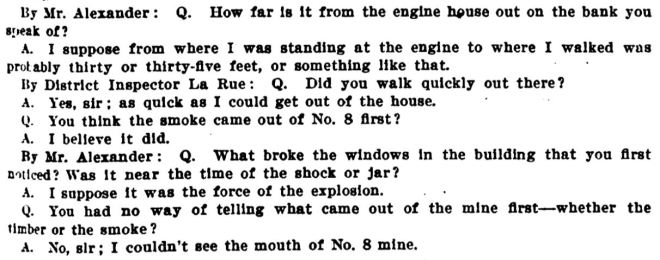

Ed Fry has been a stationary hoisting engineer at #6 “since it started”, about 6 years. He is examined by Inspector Paul.

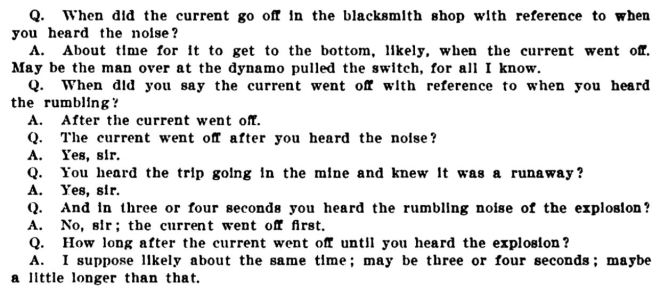

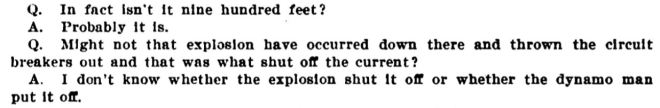

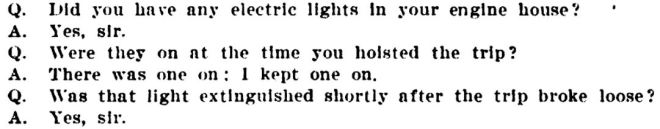

Ed was working in the engine room on Dec. 6 and knew something occurred when the trip broke loose, left the rope which caused the hoisting engine to speed up. He says he had no knowledge of what had happened to the train before he actually left his post in the engine room.

However, Ed can not recall if he was still in the engine house or in the doorway when that light went off, but he knows that he heard no sound of the explosions and only felt the “jar” while standing in the doorway. He says he stayed within the doorway as the concussion continued and first learned of what happened when a fireman from the powerhouse “came across and told me that No. 6 had exploded.”

Ed says he then went to the power house, “the lower side there, next to the river” where he observed “smoke and dust coming out of the air shaft” of #6.

Ed is not sure how long it was between the time of the trip breaking loose and the fireman telling him of the explosion.

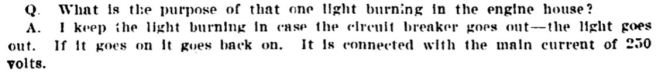

Ed says that if that light goes out while he is pulling a trip he stops pulling because it is “likely to have a wreck.” Ed does not really answer the question of what the light going out indicates other than it isn’t necessarily an indication that the wrecked trip tore down wires when it went back into the mine. “Sometimes the circuit breaker goes out frequently during the day” and turns the light off, he says, which could simply indicate some other kind of “heavy work” being done inside of the mine and not necessarily a wrecked trip.

Ed confirms that, if the trip breaks loose, the ropes which were attached to the train do not “rebound” back. Rather, the engine simply “speeds up and takes up the slack.”

Ed also believes that the trip was stuck at the knuckle for, “Probably ten minutes.” However, he does not know exactly how many were on the trip as, from his vantage point in the engine room, he could only see “one or two” once the train arrived to the tipple. He confirms that the entire trip broke loose and went back and says that “a minute” probably passed between the time the trip broke loose and when he was notified that the explosion occurred.

Ed does recall that some empty cars had gone back into the mine on a day he was working, but he can not recall how long ago this occurred or if that wreck caused the light to turn off in his engine room. He can confirm that those cars were not coming out of the mine, but were in preparation to be lowered into #6 when they went back.

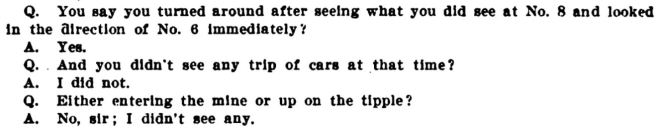

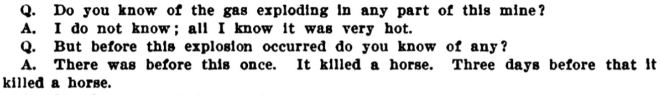

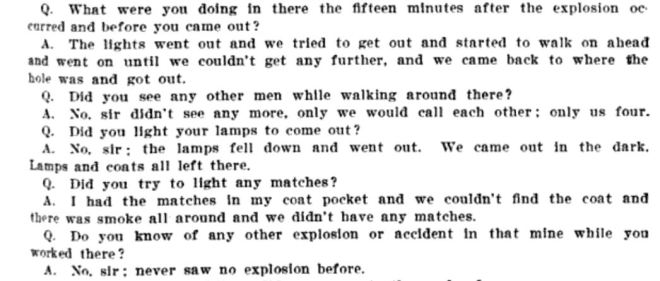

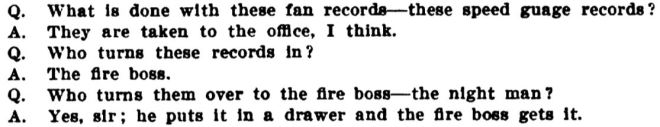

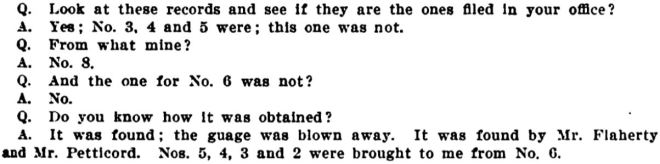

A.H. Yost has lived in Monongah for 9 years and runs the fan on the night shift for #8. He is examined by Att. Lowe.

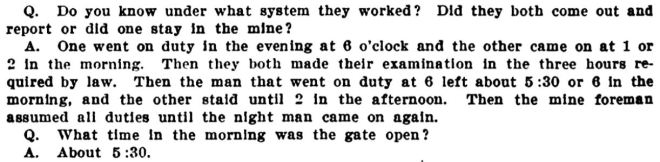

Yost confirms that William Bice runs the fan during the day shift and died in the disaster. He says that there was no one else who worked his night shift for the fan and that he did work on the night before the explosion and left his post around 5:30 or 6 o’clock a.m. on the 6th when Bice took his place.

Yost confirms that the fan ran “all night” without stopping. He states that the pressure gauge for the fan records the pressure and is changed “every twelve hours” when they change shifts. He states that the sheet was changed at 12 o’clock that night. He knows that night Pete McGraw and Patsy Kerns were the fire bosses on duty in #8 the night before the disaster, however, only McGraw is still alive. He says he only knew of two fire bosses for #8 and one foreman, John McGraw, though he assumes McGraw had an assistant.

Yost says it was he who changed the gauge sheet on that night, as he “sometimes” would and that night he “hung it on a nail and the fire boss got it.” Yost presumes that the fire boss took the sheet to the office but he has not seen it since that night.

Yost is asked what the gauge was reading that night when he took it down, but he does not know nor does he know the average speed typically indicated on the card.

Att. Lowe asks if #8 was working on the 5th, to which Yost responds that the fan was running but the mine itself was not. Yost says that he took over Bice’s place at the fan on the evening of the 5th and that the fan was indeed running at that time.

Yost says that he was at home asleep at the time of the explosions and tells Mr. Alexander that fire boss Pete McGraw collected the fan records the morning of the explosion, “I suppose, about 2 o’clock.” He is then asked about the last time the fan was stopped at #8. “I could not tell you. They generally stopped it on Sunday, if they stopped at all, to do packing or something” but he does not believe it was stopped on the Sunday before the explosions.

It is reported in the Fairmont West Virginian on this same day by a courtroom reporter that, right after being asked about his whereabouts at the time of the explosion, “The witness said there was a large volume of smoke emitted from No 6 which lasted about 6 minutes. The smoke was continuous. There was no flame.” (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 1)

However, this part of Yost’s testimony is absent from this author’s copy of the Inquiry. (Page 277 of Inquiry)

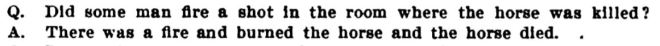

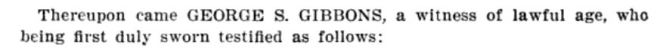

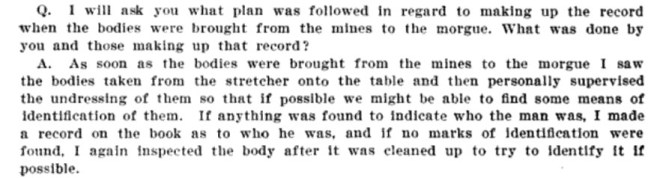

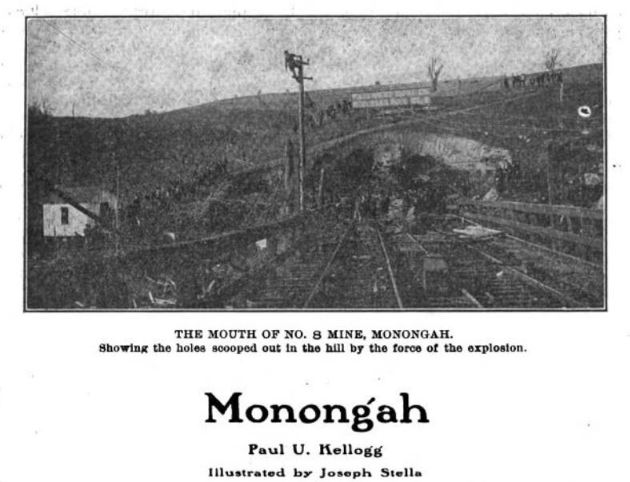

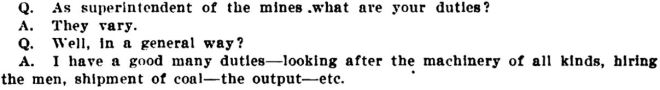

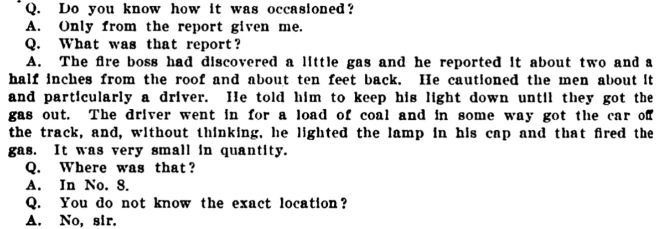

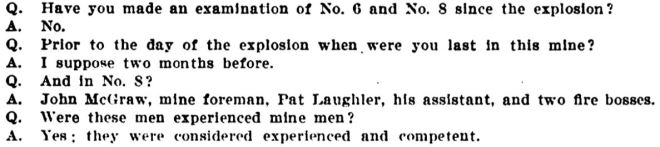

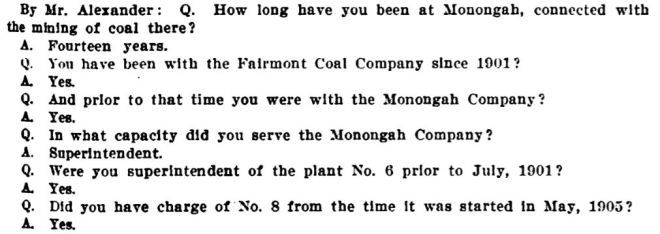

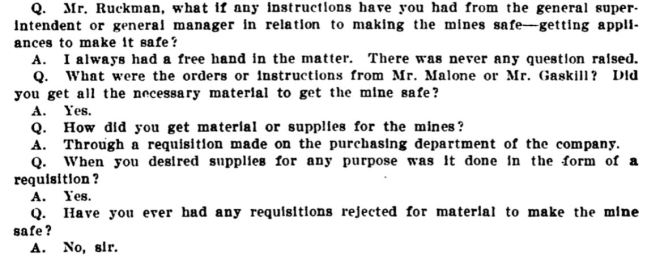

A.J. Ruckman has lived in Monongah for 18 years and is the Superintendent for #6 & #8 mines. He is examined by Att. Lowe.

Ruckman was in his office with the outside foreman, Mr. Charlie Dean, at the time of the explosions and therefore did not see them occur. “The first thing we heard was the loud report and severe concussion.” Charlie Dean then stated, “There goes No. 8 boiler.” They then “went out on the porch and looked toward No. 8, as that is where the report sounded, but there was nothing visible—didn’t see any smoke or anything.” Ruckman and Dean were then “attracted to No. 6 by a loud noise and looked down and the smoke was coming out of the air-shaft pretty strong, under high pressure.” Ruckman says he turned to Dean and said, “From the appearance it looks like No. 6 fan house is damaged. Get the men and material there as soon as possible and I will go to No. 8, and if that fan is not damaged, we will reverse it.” Unfortunately, the fan at #8 was badly damaged.

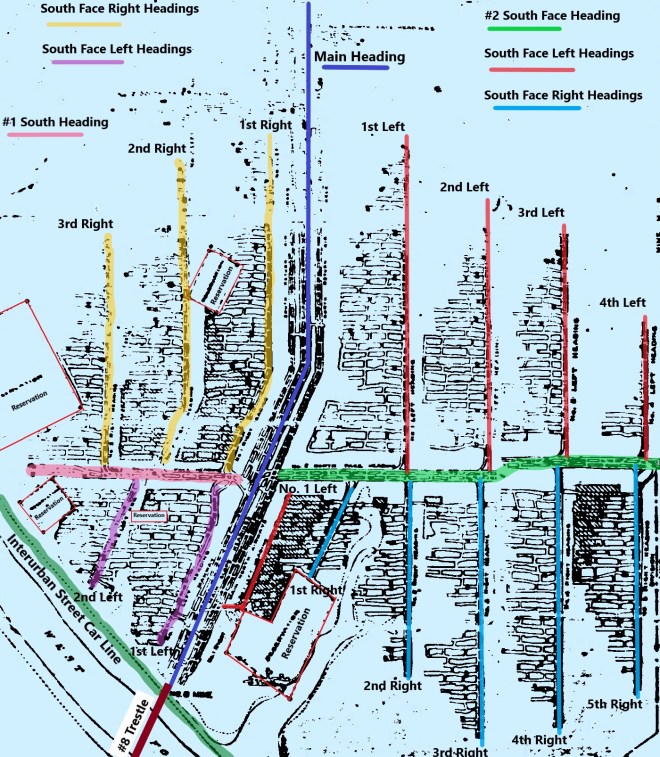

Ruckman says that the coal is hauled up the slopes and out of the mines in Monongah with “electric locomotives on the main haulway” then a stationary engine with a wire rope hauls it the rest of the way. He is asked about how long #6 & #8 have been in operation to which he replies that “No. 6 was started in 1900, and in No. 8 the ground was broken on the 12th day of May, 1905.”

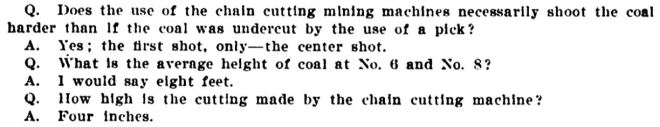

Ruckman says that a “great deal” of the mining is done with an electric mining machine; “A seven-foot undercut chain machine. Some of the work was done with a pick, in case of a bad roof where the machine couldn’t work, or pillar work.” He says that the part of the mining done by the chain machine produced “Small coal—dust in it,” and a “considerable” amount of it produced on the first cutting.

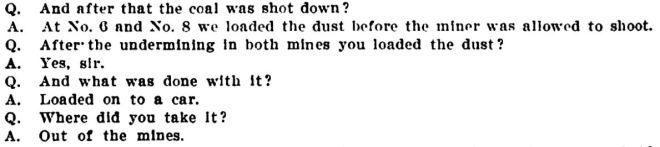

Ruckman states that no watering was done in the rooms before shots were fired, the dust was loaded and removed then the coal was shot and loaded by the miners.

Ruckman can recall that Tony Pasquale is the “regular man” to water #8 mine and that he is still alive, but “at No. 6 it was a different motorman—whoever the pit boss would designate.” He says that there are no motormen from #6 who survived the explosions. He can not say how often or necessarily what part of the mines were watered as that is “the pit boss’s duty” and none of them survived either.

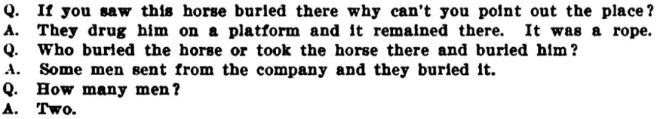

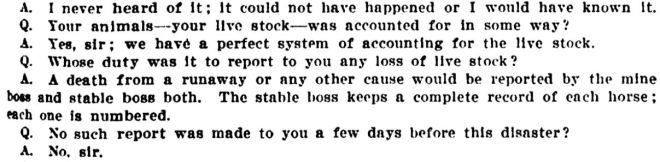

Ruckman says he neither knows nor has heard of any accident or explosion in either of the mine just prior to this one. He is asked about Peter Urban’s testimony of “a horse being killed by gas as short time before this in No. 8”, possibly just 3 days earlier.

Ruckman states that Ben Coon was stable boss for #8 and Charlie Dean “has general supervision over the work.” He says that such an accident would have been reported by the pit boss and stable boss, including a description of the event. However, the pit boss for #8 is no longer living to account for this.

Ruckman confirms that there was a “small explosion of gas” in #8 which slightly hurt a horse “about two months” prior. He says the horse’s ears were burned but really no other damage and the horse was back to working inside again within “six or seven days”. This same horse was working on the day of the explosion and killed in the mine.

Ruckman states that the employees were furnished with a copy of the mining laws in the form of a printed pamphlet. Att. Lowe hands Ruckman a pamphlet to which he confirms is the same pamphlet that was distributed to the miners about “two or three months” prior to the explosion. “They were given out as soon as we got them.” He confirms that the “card of instructions” was tacked up outside of the mine openings in seven different languages. “We had them up in different languages for several years, but after the change in rules they were put up immediately.”

Ruckman believes he made it from his office to #8 in “possibly five minutes.” He found that the “danger signal”, which warns if the mine is in a dangerous state, at #8 had been “blown away”, along with the blackboard containing the report of the fire boss. He states that he did not go over to #6 “for some time” but can confirm that the blackboard at #6 was “out of the direct road of the explosion and was not blown away.” It is currently sitting in his office in Monongah. Att. Lowe asks him to “bring it down in the next day or so.”

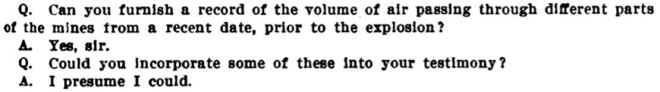

Ruckman confirms the fan operators’ testimonies that the records for the fan house are taken by the fire boss to the Monongah office, however, he says that he only has the records for the 5th and prior, not for the 6th.

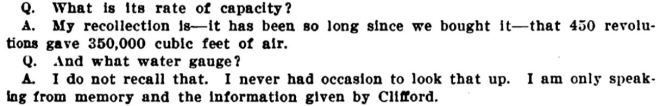

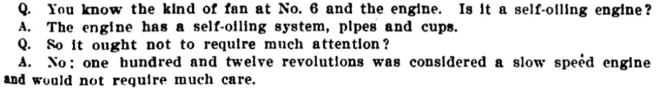

Inspector Paul asks for the dimensions of the fan at #6 to which Ruckman replies that it was a “triple fan, made by Clifford” that measured 9 x11 feet with the larger dimension being the fan’s diameter. Ruckman gets weekly reports on the fans.

He is asked the same question about the fan at #8. He says it was a “Connellsville fan made by Lepley—8 by 22.” He does not know of it’s capacity, however. “I never saw the rating. Whether if would hold up or not I don’t know, but it makes over 220 feet of cubic air per revolution.”

Ruckman testifies that no dynamite was used for blasting in the mines, but rather “3F black powder” is used. He says that the drilling for the blasting is done manually by the miners themselves, “except one face at No. 8” (which one, he is not sure) where “A contractor by the name of Preston had a portable Jeffrey’s auger and he worked four or five men.”

Ruckman says that there are no regulations to the amount of powder to be used in the blasting; “only what instructions the pit boss would give the men.” He also states that they do not keep the records of the pressure charts from the fan but that they are mailed to the general superintendent in Fairmont. He states that the charts are “a record of whether the fan man is doing his duty.” Ruckman explains that, “if the engineer would allow his steam to go down or slow the engine down to take it easier; it would show instantly.”

Ruckman is not sure if the electric chain machines cause a “greater quantity of fine dust than would be made by pick mining”; he figures “that would depend on how it was run.”

Ruckman presumes that shots are done in threes—“the same as the heading”. “One shot is placed in the center, shot out and loaded up, and the other shots are placed a foot or so from the rib.” The powder is issued in 5-pound cans and he does not know of any instance where men were burned by the ignition of gas prior to the explosions. He states that the driver of the horse that was burned some months prior, Fred Stubbs, was not hurt and is still living.

Ruckman says that the foreman and fire bosses meet “once a week” to discuss the conditions and safety of the mines. He states that David Victor was the general mine foreman “until recently”. Victor is now an inspector for the company and there was no general foreman at the time of the disaster.

Ruckman recalls that Victor was in the mines about two weeks prior to the disaster and got a copy of his report which stated that the conditions of the mines were “good”.

Att. Lowe hands Ruckman a photograph “of a blackboard with some writing on it”, which Ruckman identifies as the “Fire boss’s blackboard on the morning of the 6th.” He is familiar with the name L.E. Trader as a fire boss and confirms that he still lives. The court room reporter for the Fairmont West Virginian points out that, “in three places there were traces of gas” marked on the board in the photograph. (FWV 01.07.08 pg. 1 & 4)

Lowe then asks if Ruckman has a copy of the inspection report. “No; not with me,” he replies, but expects that he can produce it if needed. Ruckman explains that he never actually sees the Inspector’s reports as they are given directly to the mine foremen.

Ruckman explains that the cuttings and dust are loaded up before the coal is shot as it is dangerous if the dust is dry; “It is a matter of precaution.” He has charge of 2 other mines in town and says that the method of mining and shooting the coal is done “practically the same” in all.

Coroner Amos asks about what is done with the dust after it is loaded. Ruckman simply says it is loaded and “taken away”.

Mr. Alexander wants to know how far #6 had been driven and developed when FCC took charge in 1901. Ruckman is not positive about the exact depth but acknowledges that it has increased significantly since. He says that the same exhaust system from the Monongah Company was used when FCC took over and is still used now, as well as how the coal is hauled; “The only change is the increased number of locomotives on account of the increase in the length of the haul.”

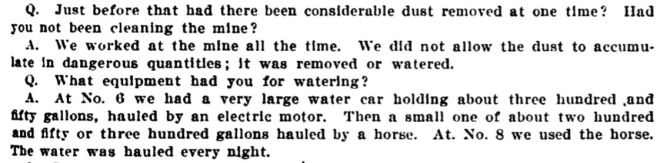

Ruckman states that the mines are watered with a 300 gallon car in #8 and with one large car, about 350 gallons, and one small car that holds around 275 gallons in #6. They are filled at one of the three pumps located through the mine and moved via electric locomotives. “The end of the car is perforated and filled with wooden plugs. They take them out and spray the track.” However, he confirms that this does not spray the ribs, just the tracks.

Ruckman states that it was up to the mine foreman to determine when watering needed to happen and where. His instructions on watering were just to “keep down the dust—not to allow it to accumulate—not to take any chances. ”He says it was watered “very often” in the colder months but the summer time doesn’t require as much watering.

A large iron gate is placed at the mouth of both mines so as not to “allow anyone in until the fire boss had completed his examination.” The fire bosses Ruckman knows of at #8 are “Kerns and McGraw”.

Ruckman lists 3 fire bosses for #6: “Jim Lyden, Mr. Morris and L.E. Trader.” He says their system was the same as #8 and that at least one fire boss was there “practically all the time.”

He cites the foreman for #8 as John McGraw, his assistant as Mr. Laughler, and the foreman for #6 as Tom Donlin, his assistant as Mr. Rogers.

Ruckman has known John McGraw for 12 years or so and says that McGraw worked in Pennsylvania prior to Monongah. Though he is not sure of the experience McGraw had in Pennsylvania, he considered him “Good—well posted” in his capacity as mine foreman. He believes McGraw had been a foreman for about 2 years prior to the opening of #8 as he was transferred from foreman in #3 to foreman in #8.

He says that John McGraw “first started in Monongah, helping his father. He was then only fourteen or fifteen years old. After that he was driver boss and gradually worked up.” He had worked in almost every capacity, “from trapper boy up.” However, he was never a fire boss as “he never worked in #6 and that was the only place we had a fire boss until we opened No. 8.”

Ruckman says he has known Tom Donlin, foreman for #6, for “about the same length of time.” Donlin also worked his way around the mine as “a miner for a while, then a machine man, then assistant boss, then mine foreman.” Ruckman says that Donlin was “a man of considerable experience in Pennsylvania and all of the coal mines, I think, in this state.” Though Ruckman is not sure if Donlin had any formal training or instruction on mining, he knows that John McGraw received some “from this Scranton school.”

Ruckman says that he has known the fire bosses for #8—Pete Kerns and Pete McGraw—for 10 or 12 years. He says that Pete McGraw had been working there at least 14 years “in nearly every capacity.” Pete had been “a miner and a machine man and boss driver” but had taken a course at the Scranton school and this was his first fire boss position. He is not sure if Pete Kerns also took the course at Scranton but includes that he is “a man of considerable experience.” Likewise, he is sure that Trader has also taken the course, but is not sure if Morris did. Morris had been in Monongah around 4 years and worked in Pennsylvania prior to then.

Tim Lyden has also been there around 12-14 years but Ruckman only acknowledges that Lyden “had the same experience”. Ruckman is not sure if any of the men carried fire boss certification from Pennsylvania but he thought of them as competent and qualified. “I think they were—all five of them. They were very energetic and loyal.”

Ruckman cites L.L. Malone as general manager of FCC and J.C. Gaskill as general superintendent. When any inspectors visited the mines, they reported to Gaskill who in turn provides Ruckman with a copy with instructions as well as two more copies of the report—one for each mine foreman.

Ruckman says these materials were furnished “very quickly” whenever requested and if needed in a hurry, they could be ordered by telephone “to be followed up by a requisition.”

He says that the Lepley fan at #8 “showed up in our test to be a very good fan”, one of the best in the U.S. and among the largest capacities available. It had been in use at #8 for about a year and they never had much difficulty with it.

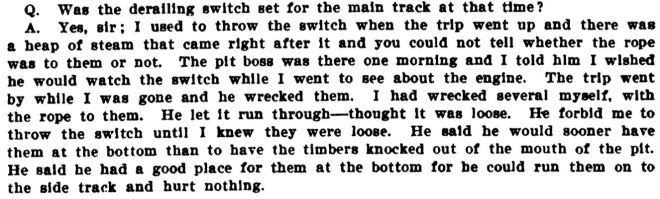

J.H. Leonard was in charge of the Capell fan at #6 and Ruckman says he had been “since we started—six or seven years.” Ruckman says that Leonard was “put in charge” of the derailing switch “immediately” after it was installed by “Donlin’s track man”, “over a year ago.” Ruckman says he told Leonard “if a trip went in the mine and it was necessary for him to oil the fan for him to call a carpenter to attend the switch and not to leave it under any circumstances.” He acknowledges that Leonard “frequently got someone to take his place” at the switch when he had to leave.

Ruckman is asked again about reports and records made about injured livestock. He says that these reports are “not necessarily” written reports from the start. Whoever is reporting the incident “comes in the office and reports it and we make a written report to the Fairmont Coal Company.” The stable boss “makes a monthly report of the stock and reports the loss of any” in the same manner.

Ruckman disputes Peter Urban’s testimony saying, “nothing of that kind happened. I heard that evidence yesterday. If there had been an explosion sufficient to kill a horse there must have been a man with the horse to set the gas off and it would have killed him, too.” Ruckman enforces that they have a “regular form for accidents and death reports” which must be made according to the law and no such report matching Urban’s testimony was made prior to the explosions.

More on the Monongah Disaster of 1907

How Death Gloated!: A Timeline of the Monongah Disaster and Bloody December of 1907

Who is Guilty?: A Timeline of January 1908 and the Coroner’s Inquiry