By Katie Orwig

“As an individual, you have had a very limited set of experiences. And the limitation on your experiences may have then set a limitation on your thinking—may have narrowed your thinking. And to recognize those limitations—to recognize that you may have been limited by your family, by your education, by your church, by the class to which you were born—to recognize the limitations of your personal experience, is to then enable you to perhaps go beyond those limitations.” – Howard Zinn, The Lottery of Birth

What is privilege?

Today in the 21st century most people directly associate it with wealth, comfort, inherent advantages, and power. To be privileged is to be of your paradigm and never question what lies beyond; to never see it for what it is. Because what it is, is familiar and comforting so where is the want to change that?

Those are, indeed, privileges. And there is nothing wrong or bad about any of them.

Though, they were not mine.

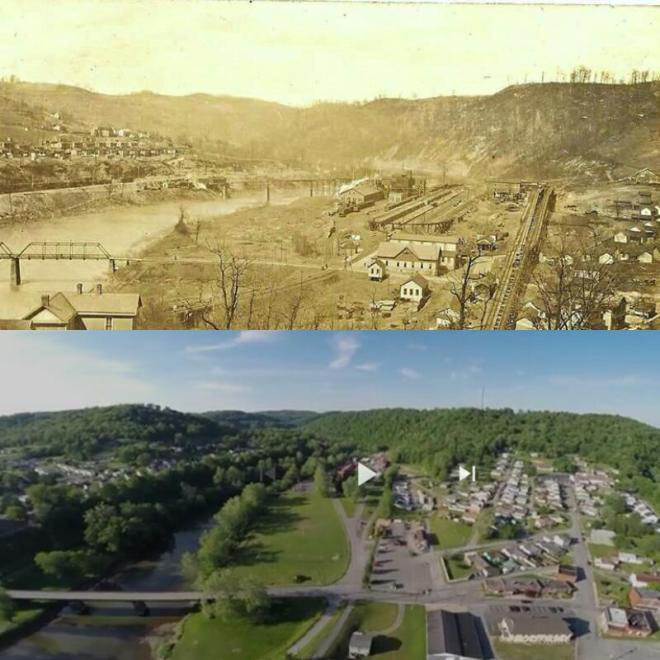

My privileges included: childhood poverty lingering into adulthood despite never-ending work; inherent disadvantages based on my simple lottery of birth which have allowed others to look down on my home and proudly say, “at least we’re not them”; learning very early on in life that the color of my skin might be the only inherent advantage I have; Stockholm syndrome from a narrative designed to get you to accept oppression as a universal reality so you will oppress yourself and others making everyone too afraid to leave their paradigm despite its obvious toxicity; and the discomfort of knowing that I lived, played, and went to school atop one of the worst disaster sites which gave the U.S. so many of its privileges—that the reason I and every other child across the country got to do those things was because innocent adults and children were slaughtered beneath my very feet, including my very own great-great grandfather.

Or do all U.S. teachers, parents, and religious leaders get that kind of ammo?

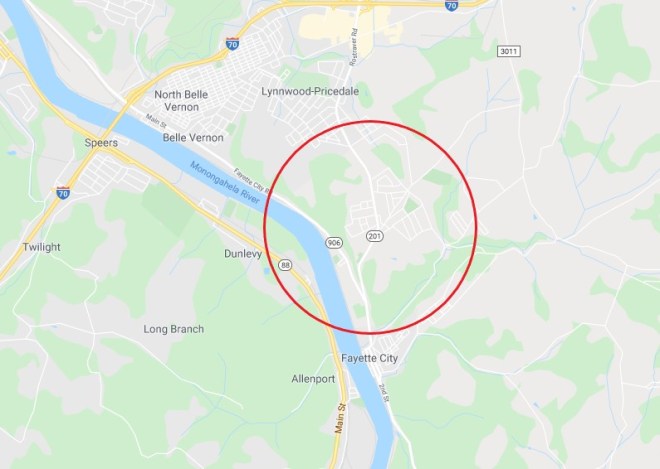

That was my paradigm and that of hundreds of other children and adults all around me in the little town of Monongah, West Virginia.

And it was, indeed, a privilege.

“There is a very partial window that is opened for you and that partial window numbs you to the impact of your actions.” – Vandana Shiva, The Lottery of Birth

What matters is the influence made by these privileges and what one does with them. There is nothing bad about privileges; we all have more than we realize. But, do we share those privileges to gain perspectives from experiences which we can’t possibly have ourselves—to gain enlightenment from one another—or to create a hierarchy of these perspectives in order to continue oppressing ourselves and one another?

Privileges explain who we are individually and as a collective, but they turn bad when they become an excuse for why we should stay within our respective paradigms. If I allowed my privileges to be my excuses, I would have been in my grave over a decade ago—just another statistic in the opioid epidemic. But they do explain who I am and I am not ashamed of them nor will I deny or desire to change them just because openly acknowledging them forces others to uncomfortably address their own unacknowledged privileges.

Instead, I choose to share those privileges and expose the true value of them. I choose to give you the privilege of knowing just some of the things I know, but never occurred to you that you should know. And what better place to start than with my biggest inherent privilege of all? One over which I had absolutely no control.

It is a very elite few who win this lottery of birth; a very elite few who got a lifetime of listening and learning; a very elite few who get to have a relationship with this event and its people as more than just an “historic subject”; an even more elite few who were privileged to perspectives, knowledge, experiences, and insights on this event and place which no historic scholar could ever possibly have or find.

I am a born and raised Monongah Lion which gives me more connections to this place, these people, and this event—personally and intellectually—than any official historian or scholar I have yet come across. I was not just privileged to live where I lived but to be exposed to the people and their cultures, to care about them and their stories as part of my own. It is also a personal lucky privilege to have always been one who loves stories. I paid attention when people told their stories to me as a child and, at 35, I have surprisingly retained a lot of them.

The disaster was over a century ago but an odd heaviness still hangs in the air of Monongah. Anyone who was raised in it will begin to question it at an early age or simply learns to ignore it. My husband felt it the first time he came back with me for a visit, though he did not know of the disaster at the time. I was lucky enough to be one of those who questioned it early on. Though, I can’t tell you that I have any answers yet or that there even are answers to be had.

Answers really aren’t what matter. Answers won’t change the events, they can only influence our perspectives and understanding of events. But they can also influence the perspectives and understandings we have of the people involved in these events and the perspectives we hold of ourselves. The change that gets made is up to each and all of us and what we choose to do with this privilege.

There is no one living today who can be held responsible for what happened in Monongah’s gloomy past. But everyone living today is inherently accountable for the memory of that past and how we use the privileges we have gained from events like Monongah. Being privileged to this rare lottery of birth, I accept my inherent accountability and responsibility to share this privilege with you.

It will not be a comfortable experience. It will include the truths and the falsehoods, the mistakes and misunderstandings, the corrections and oversights humans are prone to make. There will be stories without endings or closure, people who play but minor roles yet their perpectives matter all the same, valuable information which doesn’t really have a ‘place’, and accounts which can only be verified by the long since dead.

There is no running narrative; no grand thesis or conclusion. This isn’t an academic adventure where I am trying to force you to see something that probably isn’t really there. Maybe you will see something, maybe not.

It will be confusing, overwhelming, and intimidating as I have no intention to lead you in any one specific direction or tell you what you should think. I hold an unyielding conviction that it is impossible for anyone to be an expert on much of anything in this world—even one’s own experiences. That all history is in the perspective of the historian is an unfortunate truth which I openly claim.

Though I have collected this information because I am working on an historical fiction, all good historic fiction is just 98% truth and 2% fictional filler. The narratives that are currently out on Monongah, even those from accredited historians, do not come close to that percentage simply because the conflicting information we do have left from this event and the way we are compelled to formally present information forces one to choose a narrative—to discredit one in favor of the other. I have done my best not to do that except where it helps eliminate redundancy. I feel it is important for you to be as jumbled and conflicted as they were on these matters. It is important that you attempt to fill in those blanks for yourself, to look for more information yourself and to make your own choice: will you take the information for simply as and what it is or will you challenge and omit that which disrupts the easier narrative?

This work I am presenting is not a formal research project, nor is it presented as one. My own narrative of this event will come in good time, but I will not attempt to masquerade it as nonfiction like so many others.

All I can do is share my research and knowledge with you for what it is.

“I think the key to any progress is to ask the question ‘Why?’ all the time. Why is that child poor? Why was there a war? Why was she killed? Why is he in power? And those questions can get you into a lot of trouble. Because society is trained by those who run it to accept what goes on. And if you keep asking questions its very destabilizing. And yet, you have to do it. Without questions we won’t ever make any progress at all.” Tony Benn, The Lottery of Birth